A long-standing tradition within Celtic culture is the treatment of language and writing. As evinced from the corpus of traditional tales and manuscripts, language and its use is imbued with an ineffable power that if one knows how to use it well will indicate that person as significant and powerful. This view of language permeated within the emerging Celtic Christian tradition, as monastics continued the linguistic training of their predecessors within their monasteries. A key aspect of this training is in the transmission of Ogham, an enigmatic script often attributed to Druids that has captured the imaginations of Celtic scholars and culture enthusiasts alike.

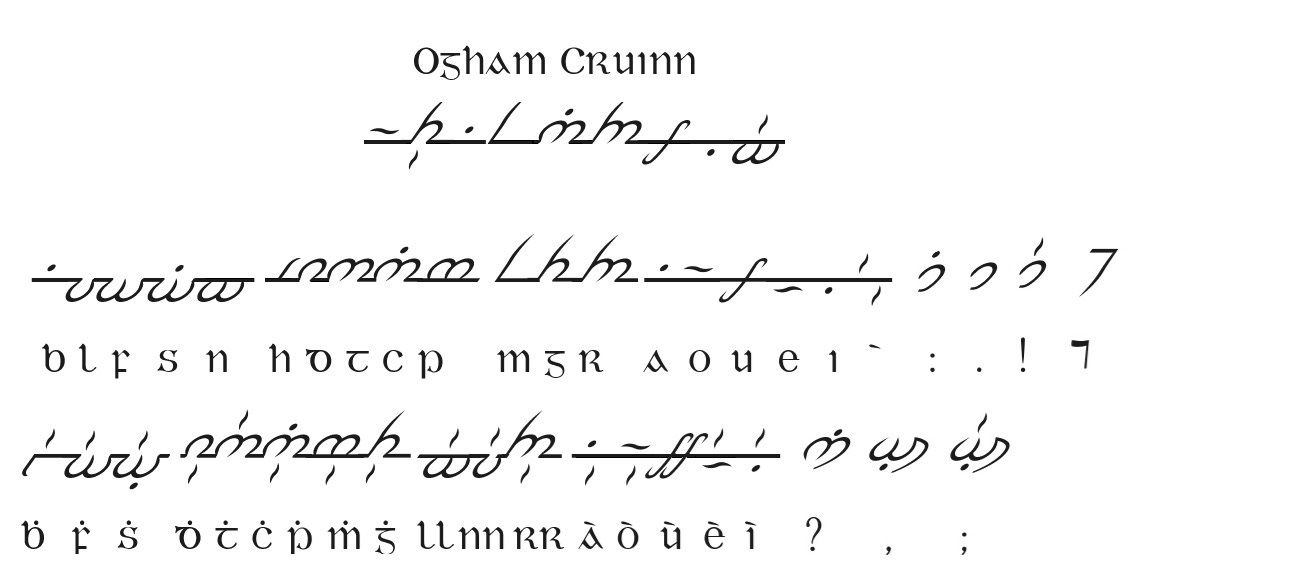

However, the Ogham often presented in books does not conform well to the Irish and Scots Gaelic spoken today as it was meant for the Gaelic language spoken centuries ago. As a collaborative project, Dr. Adam Dahmer and I have constructed a new Ogham script, named Ogham Cruinn, will serve as an introduction towards developing a series of novel ogham variations called ogham ùr-fhasanta – or ‘New Ogham’ – that conform to the standards of how the Gaelic language is written today. Within this article, the history of ogham will be explored to give context as to why this writing style is important and how to use Ogham Cruinn in writing. This will hopefully inspire a new generation of creatives to learn either Irish or Scots Gaelic, and develop their own Ogham scripts.

A Brief History of Ogham

Early mentions of ogham are present in the traditional tales of prehistoric Ireland, where they are attributed to the figure Ogma mac Elathan. Depicted as a formidable warrior and a member of the pre-Celtic mythic peoples known as the Túatha Dé Danann, we find passages related to Ogma in the manuscript In Lebor Ogaim where he is described as “a man well skilled in speech and poetry, invented the Ogham. The cause of its invention, as a proof of his ingenuity, and that this speech should belong to the learned apart, to the exclusion of rustics and herdsmen.” The earliest ogham inscriptions are dated around the 5th and 6th centuries, where they served to indicate land ownership or as a cenotaph marking where someone was buried. These inscriptions, referred to as ‘orthodox ogham,’ were written in an early form of Gaelic called Archaic Irish. While some have speculated that the development of ogham emerged through contact with either Latin or Old Norse, there is not enough evidence to conclude which writing system served as an influence. Through contact with the Irish people, ogham stones have been found in modern-day Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and the Isle of Man where some have been inscribed in Ogham adapted for Common Brittonic and Pictish.

With the emergence of a distinct Irish Christian tradition after the 6th century, orthodox ogham provided the Irish monastics the inspiration to cultivate it into a new form of writing – scholastic ogham. Used in Old Irish and Middle Irish (called ‘Old Gaelic’ and ‘Middle Gaelic’ in Scotland), this writing style is commonly found in manuscripts and may have been used for cryptographic purposes. In the article In Lebor Ogaim, ‘The Book of Ogham,’ Deborah Heyden states that, “It is probable, however, that they point to a broader interest in cryptography or secret communication that can ultimately be traced to much earlier ideas about the exclusivity of literate knowledge.” The exclusivity of learned knowledge is directly attributable to the mythical account of Ogma and is connected to the filí tradition of medieval Gaelic society, who were known for their extensive knowledge on traditional storytelling and poetic repertoire. Evidence of this is found in the Middle Irish metrical tract Auraicept na nÉces where the first three years of file entails mastering 150 species of ogham. This is a significant departure from the orthodox ogham tradition, where only one distinct form of Ogham has been found. The use of ogham also expanded to include Latin inscriptions as attested in the Annals of Inisfallen, dated to 1193.

The use of ogham continued into the early modern and modern period, where variations of the script were found in manuscripts owned by the Ó Longáin family containing Irish-language prose. In the manuscript RIA MS 493 (23 C 18), Mícheál Óg Ó Longáin (1766–1837) demonstrates his knowledge of ogham in the manner that he signs a page containing a list of Roman and Arabic numerals. In the article Ogam Script in the RIA Library Collections, Hayden explains that, “The first signature in the above image is in traditional ogam script, while the second is in so-called ‘ogam coll’, a cipher in conventional script in which vowels are instead written with one to five cs. This code appears to derive from one of the variants of ogam referred to in In Lebor Ogaim as coll ar guta (‘C for a vowel’).”

Another notable ogham enthusiast is the antiquarian John Windele (1801–1865), who intended to decipher many of the stones that he encountered. Using his knowledge of the In Lebor Ogaim manuscript, he maintained a vast series of notebooks illustrating sketches of various ogham inscriptions and variations. Hayden states that, “Windele’s notebooks offer valuable insight into the activities of nineteenth-century Irish scholars and antiquarians who sought to preserve and decode ogam inscriptions on stone monuments across the island and further afield.” Rather than discarding it as a vestige of a bygone era, the use of ogham maintained its longevity in the minds of Irish poets and antiquarians who valued its place within Gaelic culture.

Ogham Cruinn

The Ogham Cruinn script is designed to conform with Modern Irish and Scots Gaelic languages, while maintaining a connection with the earlier ogham traditions. For example, the traditional 20 letters have been contracted to 18 with the exclusion of special characters and punctuation. These special letters include lenited consonants, double consonants, and accented vowels, which are differentiated from their counterparts by the addition of an accent.

The traditional elements include the use of miniscule writing within Ogham Cruinn, wherein there are no uppercase letters. This is derived from the style of writing commonly used in Irish monasteries called Insular miniscule. The stem characteristic of Ogham has been retained, which has given the script a more cursive form of writing comparable to what is present in Semitic languages, such as Arabic and Syriac. Much like these languages, sentences are not written continuously and include spaces between words. While the alphabet has been contracted, the traditional names of all the letters are still applicable. Thus, the letter b is still beith, l is luis, and n is nuin.

.